E

Before baby seats were compulsory

And in my experience it is pure fallacy that folk who toil the earth and live of the land have a deep connection to the environment — the same way it is utter bullshit that people are friendlier in the country. Country towns are forbidding and pernicious places that should be avoided. Just watch Straw Dogs by Sam Peckinpah or Wake in Fright by Ted Kotcheff for a dose of reality to quell the romanticism of the English countryside or Australian outback.

My mate Ed always returned from school holidays spent at his cousins’ farm with diabolical stories of animal brutality and death to slake our macabre adolescent curiosities — massacring a litter of barn kittens in a shallow grave with twin barrels of a shotgun — launching themselves off the back of the moving vehicle to club a diseased ewe’s head in with hockey sticks.

Farmers certainly have respect for nature, but it is a respect derived from a livelihood of where they live and work.

And being intimately connected to the process of cultivating crops and rearing animals for harvest and slaughter immunises country folk to the anthropomorphism and fragile Disney sensibilities cosmopolitan western cultures project onto the animal kingdom.

It is evidenced by our vocabulary and spectrum of words we use to describe animal disposal. We may cull an overpopulated colony of koalas, but we’ll destroy a suburban fox or vicious dog, slaughter a cow to buy beef steak, butcher a pig to eat pork cutlets, murder a whale, eradicate wild goats, exterminate a rat infestation, dispatch old Nougat to the knackery to be rendered, put Whiskers to sleep, flush Gordie down the toilet, and take Dougall on a trip to doggie heaven when the time comes to see the vet.

I’ve witnessed my dad kill a lot of shit, and he remained notably consistent and unbiased at unloading lead into any critter that passed his crossed hairs when armed. This can also be said for my brother.

Dad killing shit

My brother killing more shit

I even woke once to a cataclysmic boom that shook the thin walls of our farmhouse. I stumbled out of my room with hand-slapped eyes and saw dad standing inside the front door using the frame as a lean for .22 Winchester Magnum. He fired again in an attempt to plug the pesky resident magpies in a nearby Marri tree that swooped on him all day while working in the field.

‘Sorry did I wake you?’

‘Um, yeah dad cos you’re shooting a gun from inside the house.’

Again it’s hard to say what measure of my dad’s upbringing influenced my bro to walk off with the .286 bolt action slung over his shoulder and go kill a kangaroo. At the time we were camped out at Durba Springs.

Durba Springs

Outback Oasis

It is a stunning oasis along the arduous and remote Canning Stock Route that traverses the Great Sandy, Little Sandy and Gibson deserts of remote Western Australia.

The Never Never of the Canning Stock Route

Looks like it’s up to me again to dig us out of the shit

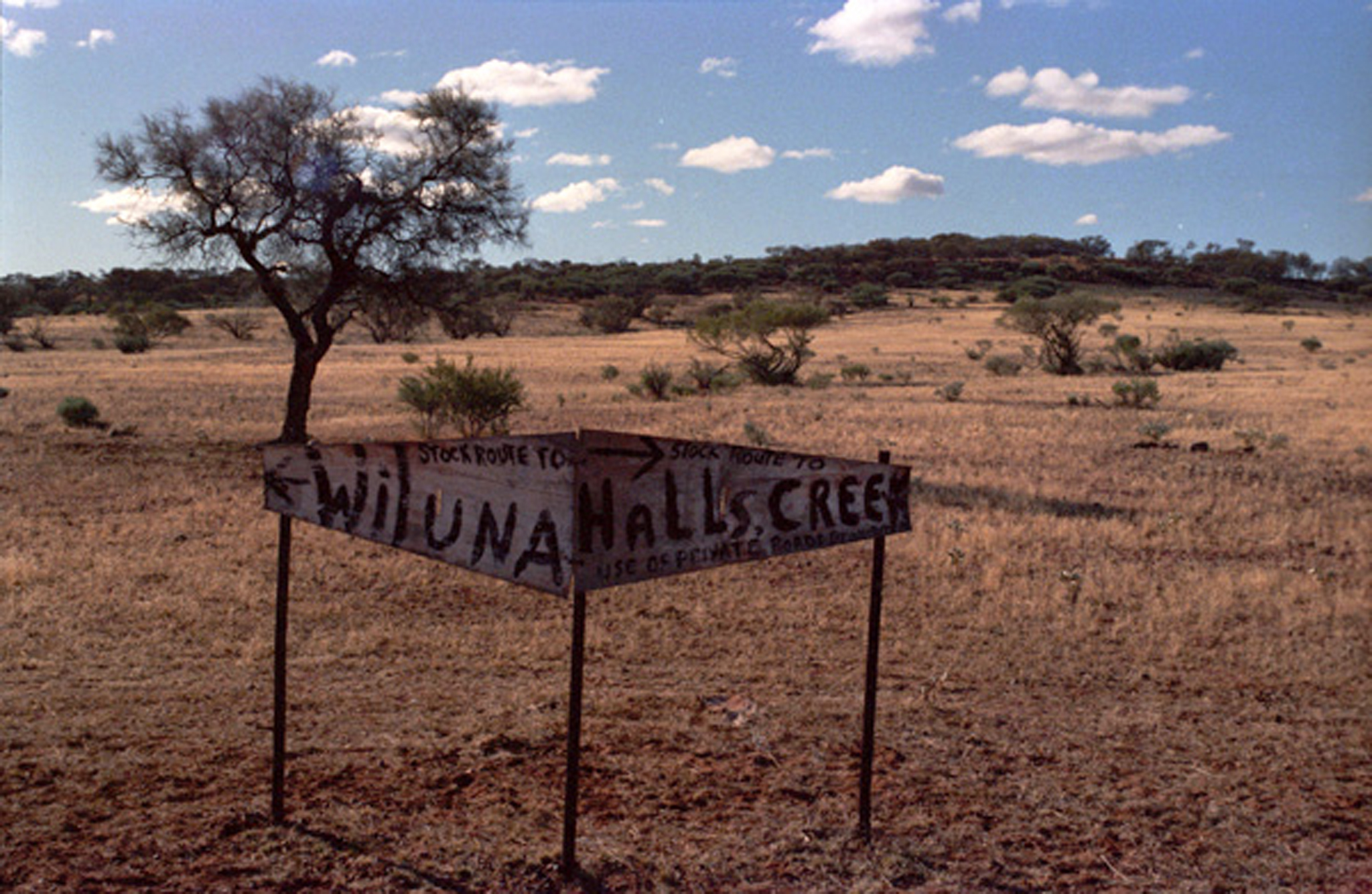

The Canning Stock Route connects Wiluna in the Midwest region to Halls Creak in the Kimberley

Our goal for the trip was to complete (survive) the 1850 kilometre journey and make it to Halls Creek Crater.

Fifty-two wells perforate the Canning Stock Route and away from Durba Springs there is scarcely another natural water source to keep stock men and bovine alive.

It was over forty minutes later when my brother returned to camp claiming he’d liquidated a kangaroo.

‘I got one dad – I shot a roo!’

‘Where?’

‘Couple of kays that way.’

‘Where?’

Couple of kays that way from our camp

My bro pointed to a vague position along the vast gloaming horizon.

‘But I think it’s pregnant cos its pouch is still moving,’ my brother added,

‘Did it have a joey?’

My brother shrugged.

Dad said we better go take a look so we got into the Pajero and circumvented the far side of the verdant spring.

I remember driving for some time and being impressed at the tenacious distance my brother covered to hunt down a kangaroo. I also found it admirable and surprising how competently my bro directed us through the Never Never to where he felled his poor pregnant prey.

Seeing the vellicating belly of the dead Western Grey made me queasy. Alien was a vivid memory in my childhood brain and I imagined the kangaroo incubating an alien larva that was now busting to emerge.

Until I reviewed the photo of my brother & his trophy roo I also didn’t appreciate how true my bro’s kill shot was — possibly cos the twitching corpse at our feet was distracting

I didn’t understand why my brother went off and shot dead a prenatal kangaroo — especially when we typically ate what we killed. And we weren’t about to eat this kangaroo. I had a tin of Irish stew with my name on it.

When I asked my brother why as we stared down at the certain infant tragedy he shrugged again in a defiant tone that suits a teenage boy’s ambivalence.

With retrospect again it’s hard to prescribe a single motivation accountable. Certainly, the inherent desire to earn respect and endorsement from my dad must have been a primary force. And who are we kidding. The honour and validation that comes with killing shit is as old as hills. And the fulfilment that comes from killing shit isn’t far behind — especially at an age when your moral compass is yet to find its true north.

I’m not sure if my dad swore something innocuous under his breath like ‘Sweppes,’ which he typical exchanged for ‘shit,’ and stronger cussing words. He didn’t hesitate. Like a James Fenimore Cooper character he thrust his big duke into the pouch of the macropod and ripped out a shivering and hairless pink infant with blackcurrant eyes and swiftly obliterated the unborn joey’s head with a downward stroke on the nearest rock.

Just as I failed to comprehend my brother’s bloodlust, I equally can’t explain this dead Twenty-eight.

I have no memory or defence for assassinating this Ringneck

Ruminating at one of fifty-two wells

Typical Canning Stock Route well

While the photographic evidence is incriminating — I prefer to think that while listless and bored at one of the numerous well stops I found this poor ringneck carcass dead of natural causes.

It didn’t stop me getting my ging out while we replenished our water supply. I recall scavenging the dirt for a choice globular stone. And when I found one that looked like it would zing through the air with true and deadly accuracy, I fired it at a murmation of zebra finches that regularly spasmed into flight before settling back into a clutch along fence post wire.

The ging and my aim were honest, and when the stone struck the belly of the twin tier of zebra finches perched on the fence wire, they discharged into an affliction of flight.

With neither the intention nor vaguest flutter of instinct to kill a zebra finch, I lacked any and all inclination to even walk over and investigate the postmortem of my shot. It was only the sufferance of ennui waiting for my dad to do whatever he was doing I eventually meandered about long enough that I found myself stood at the point on the fence line where my shot landed. I looked down and to my amazement at my feet were two dead zebra finches, legs ups with cotton white bellies pointed to the sky.

I was old enough to be familiar with the old idiom, ‘kill two birds with one stone’. And like most idioms such as ‘one bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’ they were nonsense used by old people to implicate caution, gratitude or appreciation at how formidable life can be. But it wasn’t lost on me that literally killing two birds with one stone although desirable, was set against a general conformity of life that it was always a highly difficult and unlikely challenge.

I wonder if the fact that I did kill two birds with one stone so young in life influenced me and my killing ways. Did it foster an ideal that nothing in this life was insurmountable or unachievable — or did killing two birds with one stone promote the fact that no matter how you look at it killing is way easier that people like to admit.

Follow or Subscribe so you don’t miss My Brother Killing Shit: Part III where I further explore the history of my bro killing shit ergo me killing shit.