A

Almost 24 hours later I arrived back in Perth and logged onto Facebook. I remember noticing the CCTV images of a dorky kid and black sedan circulating amongst friends back in South Carolina and neighbouring areas. But my eyes had already gone to sleep, and I was merely skimming through my profile out of habit before collapsing into bed. Without registering any detail, I assumed it was some local story of theft or assault.

Confronted by the devastating news which continued to unfold after I woke the next morning left me emotionally bereft, as if my feelings were jetlagged much like the rest of me. Over the weekend I wondered if my numbness was a symptom of distance – which seemed odd when real distance is almost a bygone concept now, relegated by the digital age as a theory out of date and old-fashioned. Maybe it wasn’t distance so much as it was a sense of dislocation.

I wasn’t able to share my sympathy and commiseration, to join the conciliatory show of solidarity with events such as the Bridge to Peace, where thousands of people joined hands across the Ravenel Bridge. After all, grief-and-loss is as delicate as it is strong, mercurial as it is inexorable, selfish as it is selfless — and while capable of vicious retribution, its fearless propensity to unite and restore is unfathomable.

Like the many tourists and imports who relocate to Charleston, I was immediately intoxicated by the supernal Lowcountry surrounds, the historic setting and bonhomie spirit when I first visited. And charmed by the eccentric and idiosyncratic lure of the South, I fell in love in Charleston and with the city. With time the tourist veneer faded, revealing a more intimate view of the city that can’t be shown on a guided tour. Yet the contradictions, conservatism, defiant spirit and divides of ancestry and privilege intrigued me, and I grew more enamoured with the city where I have made many lifelong friends.

In the aftermath of the Mother Emanuel terrorist attack the sincere outpouring of condolences, corralled by mainstream media conflagrated debates. Aggressively seeking appeasement and ‘a need to understand’, all attention quickly turned to a flag — a flag at the South Carolina State House that literally (both physically and legislatively) couldn’t be lowered in wake of the tragedy when both the US and SC State flags were at half-staff in mourning for the nine victims of the church shooting.

A week later and the campaign to remove the Confederate battle flag from the State House in South Carolina’s capital of Columbia had gained immense traction because many people see it as a symbol of racial hatred. With support from the president, politicians including South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley, Charleston Mayor Joseph Riley Jr. and former Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney have called for the removal of the Confederate flag.

This has been supported by retailing giants such as Amazon, Target and eBay which followed Wall-Mart’s example and declared they too would stop selling Confederate-branded merchandise. More recently Apple announced it would recall all Civil War games from the App Store that displayed the Confederate flag.

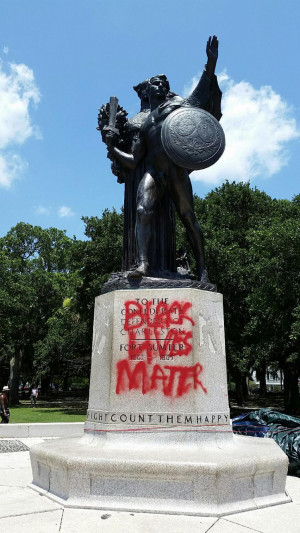

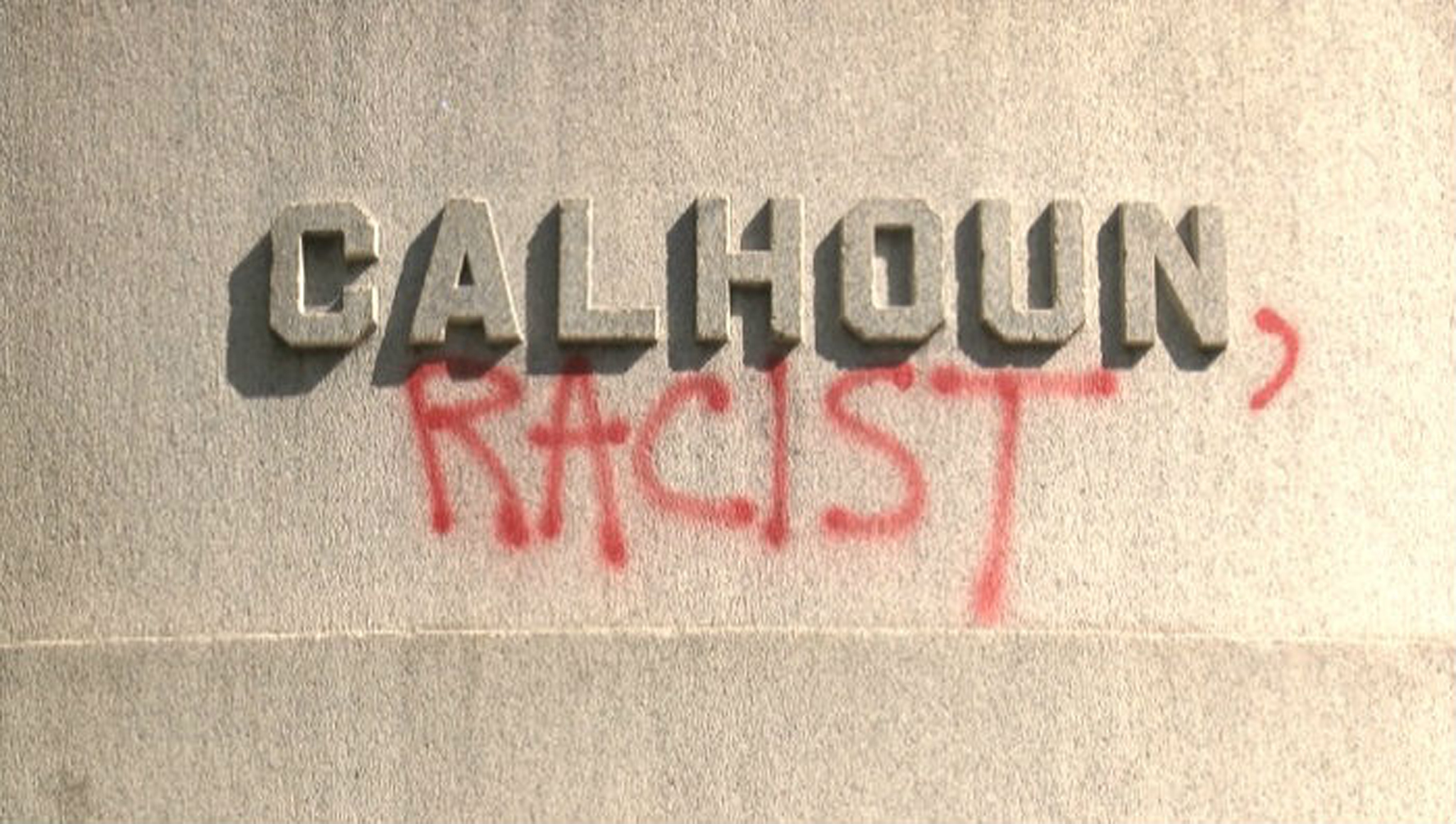

Meanwhile, at the Battery in downtown Charleston the Confederate Defenders monument in White Point Garden was defaced with a hashtag and slogan which read “Black lives matter”. Subsequently, the John C. Calhoun statue in Marion Square was graffitied with the label “racist”. President Barrack Obama then went on radio and said “nigger” and even though he wasn’t calling anyone a nigger a lot of people were offended. The momentum has since spilt across state lines with Confederate memorials across the South attracting attention and being drawn into the tide of people calling for these additional reminders of white supremacy to be taken down. As nuance and pedantry engulfed social media, white people admonishing vandalism are being called racists by other white people who applaud the graffiti as acts of rightful civil disobedience. A New America study was also released in the same week which showed more Americans died from right-wing extremist violence than deadly Jihadist attacks since 9/11. And now people are calling for Gone with the Wind to be banned.

Tearing stuff down, removing shit and busting up crap is a natural part of any cathartic process — of vetting guilt, grief and contrition. That’s what shoe boxes and front verges on collection day are for at the end of a tumultuous breakup. As societies we banish symbols and demolish places under which heinous acts and atrocities are committed. But we also enshrine symbols and places that foster enormous sorrow so we don’t forget – to commemorate our collective loss, a beacon to embody forgiveness, renewal and togetherness.

To know what to do shouldn’t be that hard — when it’s a matter of communal respect right? After all any kind of social changes requires a degree of letting go — relinquishing certain traditions, rituals and symbols that were once part of our collective identity in order to heal past injustices and move forward sensibly, progressively and compassionately for the welfare and wellbeing of everyone.

It can be hard sometimes, traversing above the feeding frenzied media to make an informed a decision of what to keep and what to let go of — especially when the real voices of those affected the most are often drowned out by people of clout lost in their own myth, caught up on camera evincing and posting their own opinions like they’re selfies of memes and martyrdom. And as a result, the very thing everyone’s trying to get rid of saturates broadsheets and touch screens. But who knows, the more practice everyone gets at letting go they might kind of like it and want to let go of other things — like branding sporting teams with derogatory and offensive American Indian names and logos, along with the tight grip around loose gun laws in the USA, which exacerbates instances of mass shootings and gun-related violence.

As a young nation struggling for an identity Australia found an enduring legacy with its own military. Known as Anzacs, they were a coalition of Australian and New Zealand armed forces who bravely fought in the First World War. To many Australians the red, white and blue cross of the Union Jack positioned above the Southern Cross on the blue-banned background of the national flag represents an inextricable history we share with the United Kingdom and as a member of the Commonwealth.

However, when republicanism gained prominence in the 1990s leading up to a referendum in 1999, our country’s flag and national anthem were again drawn into the debate. Generational arguments were bandied between loyalists leaning on tradition versus republicans claiming the flag was anachronistic and no longer held significance in our modern multicultural. This brought into focus the grievances felt by many Indigenous Australians who see the Australian flag with the canton of the Union Jack as a symbol of colonial oppression and dispossession by an invading, imperialistic force. In a completely different set of circumstances the same debate has arisen in Mississippi with calls to remove the Confederate symbol from their state flag.

Australia, along with New Zealand are amongst only a few countries in the world where changing the national flags is strongly supported. A common suggestion is to replace the Union Jack with the Aboriginal flag. In my view the Aboriginal flag is one of the most aesthetical perfect flags – for the exquisite simplicity and elegance it uses three colours to convey a people connected to a land. While incorporating some indigenous symbolism on a new flag design could represent a reconciliatory and unifying step, appropriating the Aboriginal flag in this manner could also have the opposite effect. This is because the canton of a flag can signify subjugation and division, which is why the flag’s designer Harold Thomas was also hesitant at such a suggestion. In an article published in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1994 Thomas explained,

“It stands on its own, not to be placed as an adjunct to any other thing. It shouldn′t be treated that way.”

Personally, the republican referendum in 1999 felt symbolic. It seemed a lot of Australians felt the same and with a majority happy to keep the status quo nothing changed. We retained the monarchy and our flag and anthem stayed the same.

The problem with symbols is they hold both personal and shared significance. And basically a flag’s job is to be a symbol. But it’s a hell of a job — to embody an entire nation and its people, representing the equality and diversity of their achievements and aspirations from the past through to the present and into the future. This is why flags wield immense power to unite, as well as offend, oppress, alienate and ensnare. It’s the reason I’ve never liked the idea of waving a flag (unless it’s a rainbow coloured flag with the words ‘peace’ or ‘love’ or has an image of a unicorn) because of its divisive propensity towards segregation and nationalism.

From the time I’ve spent in Charleston I consider it a home or sorts, which is a rare and fragile gift to the wending scholars of the open road such as myself. But the Confederate flag is not my legacy. The only connection I have with it is a ballistic slow-motion aerial of General Lee while watching Dukes of Hazard on television as a kid.

I’m sure Charleston will continue to do the right thing and act as a bright example — just like the last time international attention turned to the city with the killing of an unarmed black man by a white police officer. While the continuing spate of unarmed suspects being shot and killed by police is treated with an appalling lack of accountability elsewhere in the country, in Charleston the police officer was summarily fired and charged with murder.

During the process of mourning and healing I guess it’s good to remind ourselves we are all creatures of the sun. History is not universal. It has no beginning or end — the only thing it has in common wherever you are is it bleeds (Stiles). And while it’s necessary to let some things go, it’s also good to create something new — an emblem to bind us in reconciliation and peace as we move forward together.