E

Personally, I’ve always found it hard choosing a side. That’s because I’m an okapi.

Eyes Shut was my Blue Steel

Especially in the debate over the value of killing shit — when killing shit remunerated me with such a rich, thick stew of fond memories.

Killing shit with my family

Gidgeeing shit before my bro lost it trying to spear a turtle

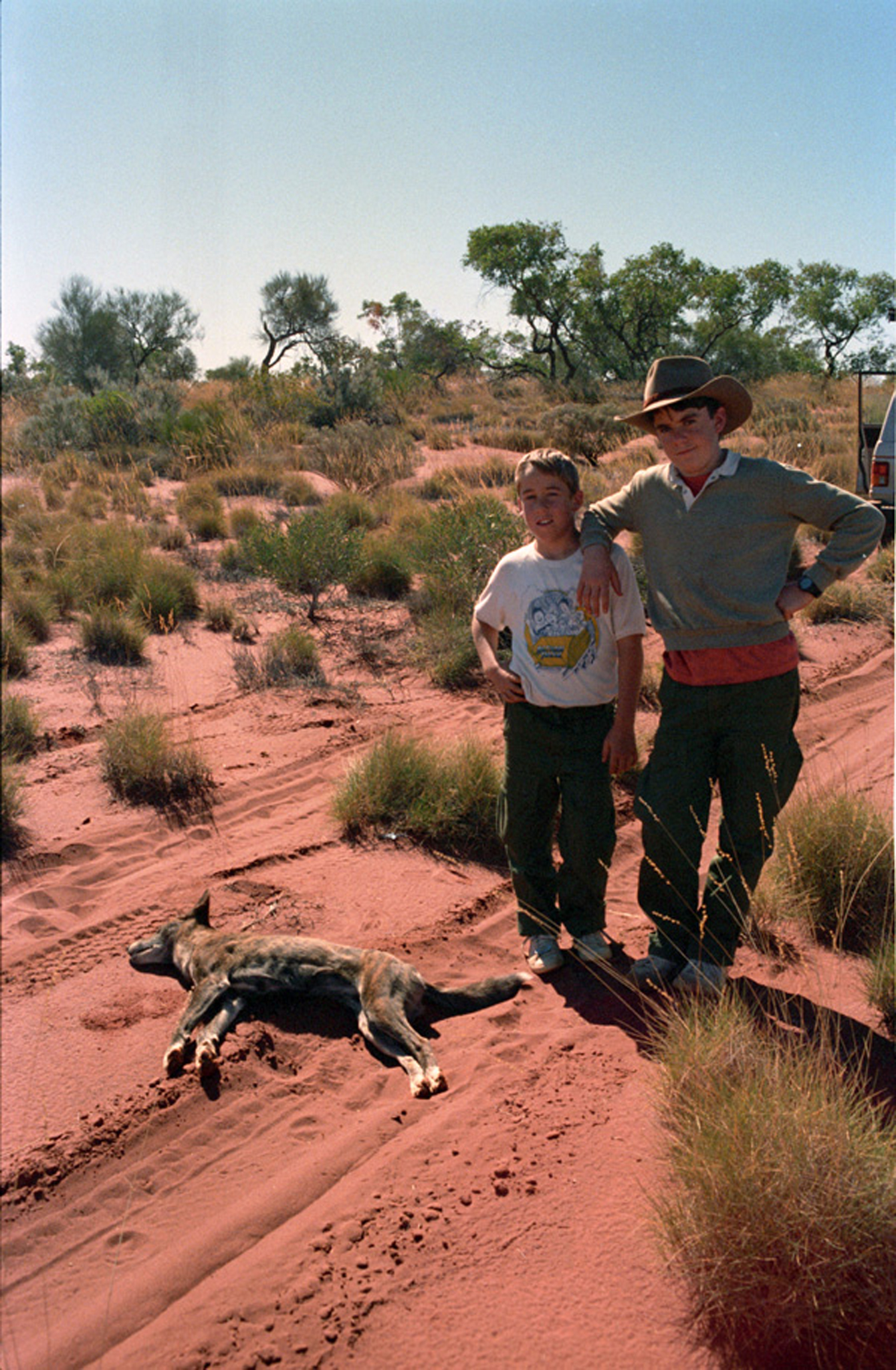

And as one of two very different brothers, killing shit was like baseball — it was something we could share. It took us on adventures with our dad and brought us together — along with that other younger looking boy who was my cute-as-hell younger sister.

This dingo died naturally from 1080 poisoned bait

Fishing at Ningaloo

In the lawless era called the eighties, when folks wielded butterfly knives, flick blades, knuckle dusters, compact crossbows and high-powered gings (like a Mad Max prequel), my dad supported the doughty agrarian proficiency of an old fashioned ging.

The tradition of constructing a ging is still a precious recollection. When my brother then I were deemed old enough we would stop by a roadside chaparral of wattle while on an outback road trip. We’d scour outback vegetation in search of symmetry – Mother Nature’s perfect prong. Of course it wasn’t just perfection I was after — I infused the process with Jedi folklore and the gravitas attached to a padawan constructing their first lightsaber. I was looking up at thickets of branches for a magical Y — one that spoke to me like a sorcerer’s wand or a hat.

27 year old ging!

#01 Carve rings into the double ended fork so the 2X leather clasps that join the rubber powered catapult grip true and don’t slip.

#02 Buy leather cord from the local cobbler and make 4X leather claps.

#03 Tailor the length of jelly rubber to suit user’s maximum resiled arm span and connect to the wooden prong via 2X leather clasps.

#04 Fashion a pouch from the tong of one of dad’s old work shoes and link to jelly rubber with 2X spare leather clasps.

In Eating Animals, Jonathan Safran Foer explores the cultural loss and cessation of family traditions that come with changing eating habits and deciding to raise his young family as vegetarian:

‘To give up the taste of sushi or roasted chicken is a loss that extends beyond giving up pleasurable eating experience. Changing what we eat and letting taste fade from memory creates a kind of cultural loss, a forgetting. But perhaps this kind of forgetfulness is worth accepting – even worth cultivating (forgetting, too, can be cultivated)…’

I have already travelled down my own personal path of conversion and redemption. Renouncing my own callow killing ways I have ostensibly been a loose vegetarian for half of my life.

However, fishing for me extends far beyond a tradition, or memory, or what Jonathan Safran Froer calls a ‘pleasurable experience’. Given our anthropomorphic tendencies I’ve always found it curious how any aversion to killing animals, even for vegetarians wanes considerably when it comes to the ectothermic world, especially those bearing gills and scales. Enter the pescetarians and flexitarians.

Cosmic ballet of fishing

In the arena of sustainability, it’s more surprising and ignorant given commercial fishing and the health of the oceans are in a much more perilous situation than terrestrial agriculture. I grew up with aquatic pets because my mum lied to us and said she was allergic to fur as way of preventing us getting a dog or cat. I also find the symbolism and spirituality of water and ocean deeply compelling.

Even my namesake which means “Sons of the hounds of the seas” has ancient ties to the mythical selkie. And despite my strong affinity for the aquatic world, fishing is a sacrifice I would still find hard to bear.

Do you get it now?

It comes from the feeling of standing on a rock alter or sandy shore with the lip of an endless, merciless ocean pawing at my toes; awed by a cosmic sunset projected across a purple sky with a plangent soundtrack of rolling combers; a parliament of gulls argue over my discarded bait; alone, connected through my feet and line in the water to the immense fluid expanse; having scored not a single bite to give away any sign of life; Bang!

The strike is unmistakable; genetic; my hand jerks forward and the shocked rod bends violently; before I know what I’m doing, my hands and body have already coordinated a response; the bravura of life and death carried in the throes of pulses, shudders, shakes and twitches up the nylon line transmits down the rod and through my fingertips like an abstruse language, recorded in my flesh and nerves; every desire, every concern, every disappointment, and every part of my me melts in that moment into insignificance; hereditary hormonal opium; whether I land the catch or not is irrelevant because the fight has already cast the real world asunder, into a latent memory; and the pure exaltation of being alive will resonate long after, postponing the real world’s return, which like a dream takes time to recall.

In my first book Loves, Kerbsides & Goodbyes I addressed the profound connection I derive from nature — how I find the closest person to who I think I am, and want to be, on my own atop a mountain, camped beside a soughing glacial flow with a backpack laden with freedom. There I’ve certainly experienced a gentle caress of enlightenment. And in my latest travel memoir Beat Zen and the Art of Dave I go much further — exploring the fanatical and bizarre vacationing relationship many of us have with Mother Nature. I also debate the conundrum of maintaining a vegetarian or vegan diet while travelling as a way of discussing what ideal should we cling onto or let go of when we’re on a path of transcendental journey.

But writing this blog I realised fishing for me is something fundamental – transcendental even. So if others find this by blowing the shit out of other animals, how can I eschew and censure other practises of killing shit.

The ultimate conundrum: could you give up this memory of killing shit with your bro for a better cause?

I don’t have children, but considered while writing this if I did, would I give up the potential of priceless memories, and severe family traditions of killing shit passed down from my dad — all for an altruistic cause?

Possibly.

But if I did, what would it change?

Would it prevent my kids from one day finding a magnifying glass in the antique desk draw, idly wandering into the back garden, and crucifying a colony of ants with bored, lazy satisfaction?