A

My dad always quoted his dad when we had an abysmal luck fishing:

Turquoise Bay – not the most imaginative name, but possibly my favourite place on the planet

‘When don’t catch anything you don’t have anything to clean.’

I valued the laconic simplicity of Tom’s fishing philosophy, because it emphasised the fulfilment of fishing came not through the results, but the process — a process that encouraged you to stand alone at sundown on a sublime beach along one of the most isolated stretches of coastline in the world.

As you may have noticed for children raised on the remote west coast of Australia, with access to 12,889 km (according to Geoscience Australia) of pristine coastline, it’s rather common to experience a photo album childhood of standing on silicon white sand, squinting into the sun with flies up ever orifice while holding a stiff dead fish.

Looking determined

Spangled emperor – at least I think they’re spangled emperor. I can’t see shit with all the flies & sunlight with dad telling me to keep my eyes open

I never want to be anywhere else

Over time I noticed in spite of collective experiences, and what we’re exposed to and how we’re instructed, we all have precepts of personalities with intrinsic differences — differences like fibres and free radicals that cause divergent sensibilities and sensitivities. The malignant disharmony and discordant wonder that is humanity.

The pride of my bro’s two large flathead & banjo shark isn’t shared by the daughter of our close family camping friends

As I grew up and as my moral fibre stiffened it was issues of animal suffering, along with the macabre and inexplicable sense of fun derived from such acts of cruelty that increasingly vexed me. I stopped trapping rabbits. The last trap I set before swearing against it I laid it out at 11 pm then woke the morning before 4 am to check on it. Full of ruefulness and plaintive concern over the possible suffering I wanted to mitigate the critter’s time spent in steel jaws with crushed leg bones, or worse, shredded by a rascally fox. And although my vegetarian status was born out of curiosity and a slow constitution that did not favour meat, I found it a pleasant consequence that I could joust in the corner of permaculutre and sustainable farming.

I still have no qualm about subsistence hunting. And despite being vegetarian I defend this freedom. If the practises of the meat industry were transparent in western culture — if people were exposed to slaughtering animals for their own consumption it would promote much more intelligent debate on all sides about sustainable eating and farming practises. It is what I liked most about my brother and me killing shit. We typically ate everything we killed. It instilled a deep respect for guns and animals, and the proud sentiment derived from fishing and hunting was unequivocally unrelated to perverse aberrant pleasure of gratuitous trophy hunting.

That was the motivation, at least for me when we drove up to Bindoon Lake each year for the start of duck season. I’m sure my dad drew on a much richer history of fraternal adventures — hanging out with mates and brewkis and guns in his youth and killing shit.

I have headlight memories of driving at night up on the eve of duck season, listening to my brother’s cassette tape music collection – Billy Joel’s Storm Front, Jimmy Barnes doing Barnstorming, Noiseworks and Midnight Oil.

Bear in mind there was no iTunes, Spotify, Grooveshark, Pandora or YouTube back then. Maybe in super cities like London, NY and Dublin there was a bootleg subculture. But in the most isolated regional capital in the world the only way you could obtain free illegal music was to walk into a music store (yes, they did exist once) and shoplift an album. And there was no ability to purchase a single song, so you were stuck with an entire album, where commonly more than half the tracks were shite — so you spent the whole time stood in front of the stereo (cos there was no remote), or with your Walkman in your hand FFing and REWing.

CDs might have existed but they were beyond the fiscal realm of ordinary kids. And man, without lasers, and digital technology, back when duck shooting was legal, and we drove up to Bindoon, unless you were lucky enough to have a mate with money who had twin decks that you could score compilations tapes off, you couldn’t do shit except pay a fukn lot for a cassette tape, which you only bought because of two, possibly three songs.

Typically we travelled the night before the duck shooting season began because it started at the rather quaint time of sunrise. And in the middle of summer this = really fukn early, especially when by the time dawn broke and a sonorous air horn sundered the morning serenity with an enfilade of gunfire, a self respecting hunter would already be waders high, locked and loaded, marked out in a rather parlous spot amongst all the other local Aussies, and immigrant Italian and Greek hunters in the middle of Bindoon Lake.

And on the eve of the duck shooting season, at least in 1989 our trip coincided with the Bindoon Rock Festival, featuring Jimmy Barnes!

Bindoon Rock was an incendiary three day, outdoor rock festival on private land that boasted only four rules:

- Rule #01 No Byo

- Rule #02 No Dogs

- Rule #03 No Aggro [‘Aggression’ for my international readers]

- Rule #04 No Glass

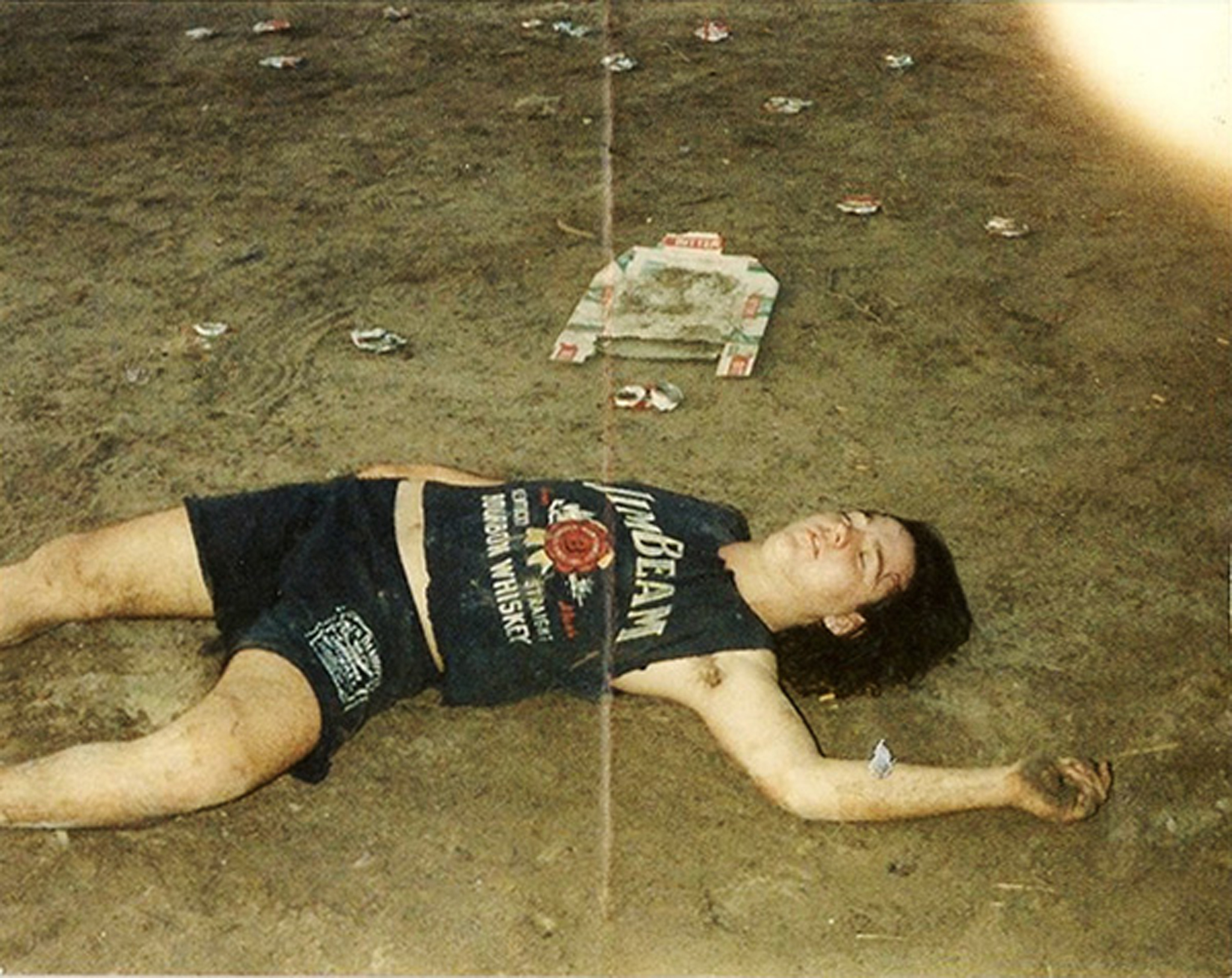

However I’m not sure how stringent the rules were enforced

Based on photographic evidence I think the rules acted more like guidelines or suggestions

So as the city peeled away from the roadside on the modest one hour drive north, a cavalcade of bikers and their girlfriends, along with beatings of bogans and other eccentrics from the fringes that I never knew existed started to accumulate on the Great Northern Highway, all heading to the same joint.

And each time an overtaking lane broadened the single lane highway, an enthralling cast of characters and vehicles passed my window. I can’t say this experience was the seed that sprouted my peregrinating nature, but I think it certainly influenced my proclivity for prolonged overnight travel on overland escapades and adventures.

What appeared essential were mullets, beards, leather and two-wheel transport. I enjoyed the trip infinitely more than duck hunting, which was incidentally banned the following year in my home state, and has remained that way ever since. And given my personal experience it is no wonder duck shooting was made illegal.

Being an old farm boy my dad had deft hands when holding firearms and grew up with a different sort of respect to animals. And my older brother was always convinced of his gun totting abilities, no matter how validated, or proven they were — like an arriviste with a loose hand-me-down reverence to animals from my dad.

At the time it seemed somewhat reckless of my dad to give my brother a shotty — mainly because I didn’t get one. And without discussion it appeared I was designated the role of hound dog – deigned to flounder through a lake, figuratively named, because in reality it was a putrid swamp. I’d frantically wade through the reeking effluvia of fanwort to collect fallen ducks then twirl their limp necks that crackled like loose cartilage to grant them death.

My dad took charge of the Berreta side-by-side. And my older brother was deemed responsible enough to wield the Winchester under-and-over because he was three years older than me. But this didn’t surprise me. My brother was always getting shit I didn’t cos he was older.

There was the famous case of Mum’s UK Holiday, which when announced at a Brady Bunch style family meeting generated an interplanetary ‘Fuk yeah’ in my head. This was because we had a tradition in our house that each time one of our parents went on a plane, one of us kids, in descending order, got to accompany them.

Since I could remember my dad had been on a plane twice for work. My older brother went with him to Canberra, then my older sister got to tag along on a second trip to Melbourne. Mum’s UK Holiday also coincided with my birthday — talk about jackpot. I could feel the glow and hum of a veritable neon arrow blink madly above my head. My arm was cocked, trembling with anticipation to yell, ‘Suck a boondy’ to my older brother and sister for the imminent announcement that I’d be accompanying her to ol’ Blighty.

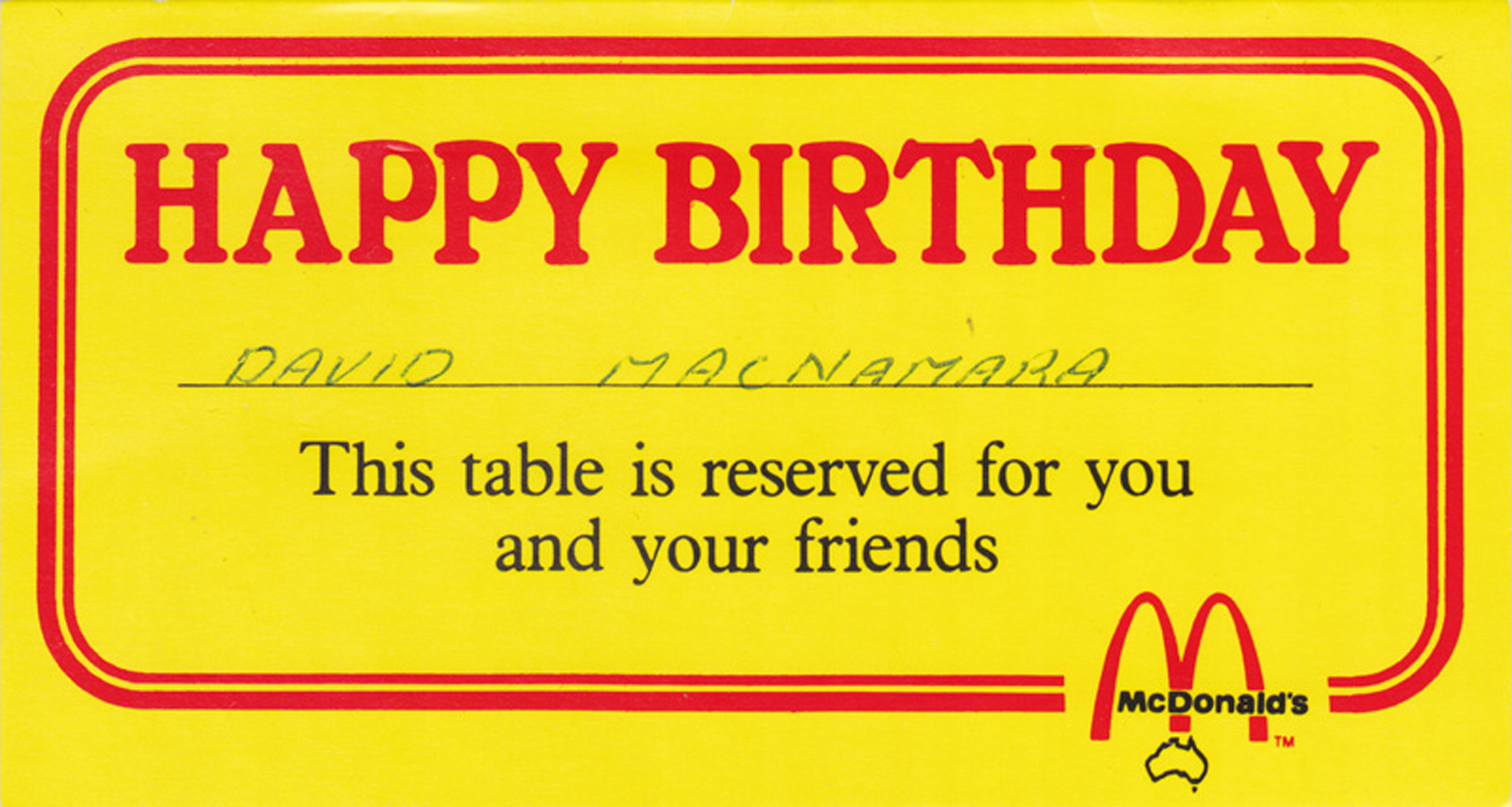

Then my mum announced she was taking my older brother — apparently I was too young, which although legitimised, did nothing to ameliorate the deepest sense of injustice I had so far found in the known universe. And instead I spent my birthday at McDonald’s with my dad and sister and a Neapolitan ice cream cake, still feeling slightly embarrassed from when dad went to order and said, ‘I’ll have two Hungry Jacks’ and a Ronald McDonald-’ But that’s another story.

I do love the fact that we reserved a table at McDonald’s for my birthday

Out on the mephitic Bindoon Lake the morning had progressed well for my dad. We got separated when dad downed the last of his bag and went off to retrieve it in the thick of a swamp bush. Up until this time my brother had been shooting clouds. Suddenly a bird with suicide on its mind appeared in our collective vision – a dream of a bull’s eye flying low and directly down my brother’s raised muzzle.

The only problem was it wasn’t a duck. It was a coot — easily discernible from the large variety of both endangered and common ducks you could legally shoot at the time because it wasn’t a duck! It looked nothing like a duck. It was much smaller, which made it more furious and frantic in the air, with a beak like a blunt 2B pencil and lampblack plumage.

I tacitly presumed my brother knew all this as well-

BOOM!

My presumption probably wasn’t helped by being perpetually inculcated while growing up that older = knowing more shit.

‘YEsss!’

The coot splashed down just ahead of us.

‘What the fuck dude?’

‘What?’

‘You just shot a coot.’

I ran to grab the bird, which fibrillated with warm death in my hand to prove he was wrong.

‘See.’

‘It’s a duck,’ he resolutely insisted.

‘Look at its beak – is it billed?’

‘It’s a different kind of duck.’

‘You shot a coot.’

‘No I didn’t.’

‘The term duck-billed exists for a reason bro.’

‘Whatuwedo?’

I knew I had my brother convinced at ‘It’s a different kind of duck,’ and I love how nouns instantly turn collective when the stakes rise and people realise they’re in the shit.

‘Throw it in that fucking bush.’

And that’s what we did.

In the end dad did let me a cheeky go at shooting the shotty. The kickback sent me arse down in the swamp.

‘Keep it out of the water,’ dad shouted and hurried to take the shotty out of my hands.

I’m sure he meant to say, ‘Are you alright son?’ Like the time I rolled my student car onto its roof in a road accident and called him up for a lift home and he said, ‘Is the car alright?’ But I’d like to think my dad cared so deeply, he developed a habit of objectifying his concern with the objects nearest us in times of calamity (as most dads do).

Follow or Subscribe so you don’t miss My Brother Killing Shit: Part V where I conclude this anecdotal exploration of my bro ergo me killing shit.